Lenstra–Lenstra–Lovász lattice basis reduction algorithm

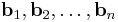

The LLL-reduction algorithm (Lenstra–Lenstra–Lovász lattice basis reduction) is a polynomial time lattice reduction algorithm invented by Arjen Lenstra, Hendrik Lenstra and László Lovász in 1982, see Lenstra, Lenstra & Lovász 1982. Given as input a basis  with n-dimensional integer coordinates, for a lattice L in Rn with

with n-dimensional integer coordinates, for a lattice L in Rn with  , the LLL algorithm outputs an LLL-reduced (short, nearly orthogonal) lattice basis in time

, the LLL algorithm outputs an LLL-reduced (short, nearly orthogonal) lattice basis in time

.

.

where B is the largest of the lengths of the  under the Euclidean norm.

under the Euclidean norm.

The original applications were to give polynomial time algorithms for factorizing polynomials with rational coefficients into irreducible polynomials, for finding simultaneous rational approximations to real numbers, and for solving the integer linear programming problem in fixed dimensions.

Contents |

LLL reduction

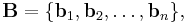

The precise definition of LLL-reduced is as follows: Given a basis

with its Gram–Schmidt process orthogonal basis,

define

, for any

, for any  .

.

Then the basis  is LLL-reduced if there exists a parameter

is LLL-reduced if there exists a parameter  in (0.25,1] such that the following holds:

in (0.25,1] such that the following holds:

- (size-reduced) For

. By definition, this property guarantees the length reduction of the ordered basis.

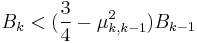

. By definition, this property guarantees the length reduction of the ordered basis. - (Lovász condition) For k = 2,3,..,n

.

.

Here, estimating the value of the  parameter, we can conclude how well the basis is reduced. Greater values of

parameter, we can conclude how well the basis is reduced. Greater values of  lead to stronger reductions of the basis. Initially, A. Lenstra, H. Lenstra and L. Lovász demonstrated the LLL-reduction algorithm for

lead to stronger reductions of the basis. Initially, A. Lenstra, H. Lenstra and L. Lovász demonstrated the LLL-reduction algorithm for  . Note that although LLL-reduction is well-defined for

. Note that although LLL-reduction is well-defined for  , the polynomial-time complexity is guaranteed only for

, the polynomial-time complexity is guaranteed only for  in (0.25,1).

in (0.25,1).

The LLL algorithm computes LLL-reduced bases. There is no known efficient algorithm to compute a basis in which the basis vectors are as short as possible for lattices of dimensions greater than 4. However, an LLL-reduced basis is nearly as short as possible, in the sense that there are absolute bounds  such that the first basis vector is no more than

such that the first basis vector is no more than  times as long as a shortest vector in the lattice, the second basis vector is likewise within

times as long as a shortest vector in the lattice, the second basis vector is likewise within  of the second successive minimum, and so on.

of the second successive minimum, and so on.

LLL Algorithm

The following description is based on (Cohen 2000, Algorithm 2.6.3), but currently is incorrect.

INPUT:

a lattice basis

a lattice basis  ,

, parameter

parameter  with

with

PROCEDURE:

Perform Gram-Schmidt:

- for

from

from  to

to  do

do

- for

from

from  to

to  do

do

- end for

- end for

(k is the stage at which the vectors

(k is the stage at which the vectors  are reduced according to size-reduced property 1.)

are reduced according to size-reduced property 1.)- if

then execute reduction subroutine RED(k,k-1):

then execute reduction subroutine RED(k,k-1):

- for

from

from  to

to  do

do

- for

from

from  to

to  do

do

- end for

- end for

- for

- end if

- Calculate

for 1

for 1  and

and  for

for  from 1 to

from 1 to

- while

do

do

- Length reduce

and correct

and correct  according to reduction subroutine in step 4, for

according to reduction subroutine in step 4, for  from 1 till

from 1 till

- if

then

then

- Exchange

and

and

:= max

:= max

- Exchange

- else

- end if

- Length reduce

- end while

OUTPUT: LLL reduced basis

Example

The following presents an example due to W. Bosma.[1]

INPUT:

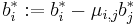

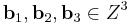

Let a lattice basis  , be given by the columns of

, be given by the columns of

Then according to the LLL algorithm we obtain the following:

1.

2.For  DO:

DO:

2.1.For  set

set

and

2.2

3.

4.Here the step 4 of the LLL algorithm is skipped as size-reduced property holds for

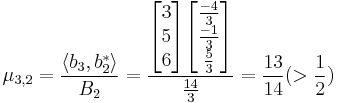

5.For  and for

and for  calculate

calculate  and

and  :

:

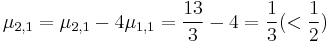

hence

and

hence  and

and

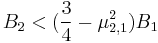

6.While  DO

DO

6.1 Length reduce  and correct

and correct  and

and  according to reduction subroutine in step 4:

according to reduction subroutine in step 4:

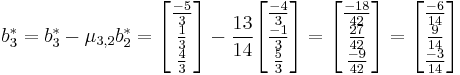

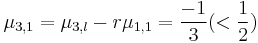

For  EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(3,1):

EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(3,1):

i. and

and

ii.

iii.Set

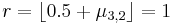

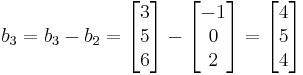

For  EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(3,2):

EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(3,2):

i. and

and

ii.Set

iii.

6.2 As  takes place, then

takes place, then

6.2.1 Exchange  and

and

6.2.2  := 2

:= 2

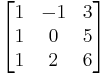

Apply a SWAP, continue algorithm with the lattice basis, which is given by columns

Implement the algorithm steps again. 1.

2.

3. .

.

4. .

.

5.For  EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(2,1):

EXECUTE reduction subroutine RED(2,1):

i. and

and

ii.Set

6. As  takes place, then

takes place, then

7. Exchange  and

and

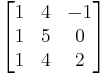

OUTPUT: LLL reduced basis

Applications

The LLL algorithm has found numerous other applications in MIMO detection algorithms and cryptanalysis of public-key encryption schemes: knapsack cryptosystems, RSA with particular settings, NTRUEncrypt, and so forth. The algorithm can be used to find integer solutions to many problems.[2]

In particular, the LLL algorithm forms a core of one of the integer relation algorithms. For example, if it is believed that r=1.618034 is a (slightly rounded) root to a quadratic equation with integer coefficients, one may apply the LLL reduction to the lattice in  spanned by

spanned by ![[1,0,0,10000r^2], [0,1,0,10000r],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3a09d44bae250cffef3372ccbf8ecfe0.png) and

and ![[0,0,1,10000]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2594c427d5b4fb0cede2634481fcdd22.png) . The first vector in the reduced basis will be an integer linear combination of these three, thus necessarily of the form

. The first vector in the reduced basis will be an integer linear combination of these three, thus necessarily of the form ![[a,b,c,10000(ar^2%2Bbr%2Bc)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c96def9c2898d637a08c9361591cff70.png) ; but such a vector is "short" only if a, b, c are small and

; but such a vector is "short" only if a, b, c are small and  is even smaller. Thus the first three entries of this short vector are likely to be the coefficients of the integral quadratic polynomial which has r as a root. In this example the LLL algorithm finds the shortest vector to be [1, -1, -1, 0.00025] and indeed

is even smaller. Thus the first three entries of this short vector are likely to be the coefficients of the integral quadratic polynomial which has r as a root. In this example the LLL algorithm finds the shortest vector to be [1, -1, -1, 0.00025] and indeed  has a root equal to 1.6180339887…(The Golden Ratio)

has a root equal to 1.6180339887…(The Golden Ratio)

Implementations

LLL is implemented in

- Arageli as the function lll_reduction_int

- fpLLL as a stand-alone implementation

- GAP as the function LLLReducedBasis

- LiDIA as the function/method lll in the LT package

- Macaulay2 as the function LLL in the package LLLBases

- Magma as the functions LLL and LLLGram (taking a gram matrix)

- Maple as the function IntegerRelations[LLL]

- Mathematica as the function LatticeReduce

- Number Theory Library (NTL) as the function LLL

- PARI/GP as the function qflll

- Sage as the method LLL driven by fpLLL and NTL

See also

Notes

- ^ Bosma, Wieb. "4. LLL". Lecture notes. http://www.math.ru.nl/~bosma/onderwijs/voorjaar07/compalg7.pdf. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ D. Simon (2007). "Selected applications of LLL in number theory". LLL+25 Conference (Caen, France). http://www.math.unicaen.fr/~simon/maths/lll25_Simon.pdf.

References

- Borwein, Peter (2002). Computational Excursions in Analysis and Number Theory. ISBN 0-387-95444-9.

- Cohen, Henri (2000). A course in computational algebraic number theory. GTM. 138. Springer. ISBN 3540556400.

- Lenstra, A. K.; Lenstra, H. W., Jr.; Lovász, L. (1982). "Factoring polynomials with rational coefficients". Mathematische Annalen 261 (4): 515–534. doi:10.1007/BF01457454. MR0682664. hdl:1887/3810.